AS A BOY, there were things that I simply could not resist: stealing cookies from the jar on Gramma’s back stairs, sneaking a swim in the Horn’s pool, or secretly reading the diary Annie kept hidden beneath her mattress.

I read her private journal, cover to cover, in a single sitting. Pizza parties. Dances. Boys. Making out. It was actually pretty boring stuff. Disappointing really. But it was exciting to read because I knew I shouldn’t be doing it! Once I finished making mischief, I slid the diary back under the mattress, making certain the bedspread and pillows were properly in place.

The next morning before church, Annie looked at me strangely and asked, “Have you been in my room?”

“No,” I said, a bit too quickly. “Why? It was probably Jay-bird.”

“Somebody’s been gettin’ into my things,” she said, studying my reaction. I squirmed a bit. “Ya don’t know anything about it, do ya?”

“No,” I repeated. “Leave me alone. We gotta go t’ church.”

Did she know? She stared at me with that look!

“Ya know what happens to little brothers who snoop around their sisters’ room, don’tcha?” she asked.

I couldn’t answer. I just looked at her, wondering whether she had found me out. But she said nothing more. She just cocked her head slightly and stared at me through those squinty eyes she had when she suspected me of something.

If Annie knew I had read her diary, she would make me pay!

A few days passed and Annie said nothing more about it. So I decided I was in the clear. Unable to resist, I slunk back to her room to catch up on Annie’s latest antics.

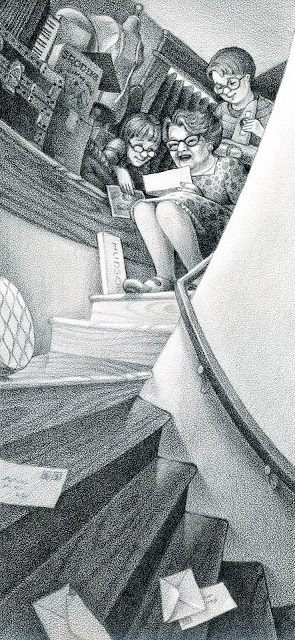

But when I reached under Annie’s mattress, the diary wasn’t there. What’s more, Cynthia was sitting on Annie’s pillow, no longer hanging in the closet where she was supposed to be. That creepy puppet stared at me like it could actually see! Its eyes were glued on me like it was keeping watch! I raced out of the room.

In bed that night I wondered what Annie was going to do to me. I knew she knew. And I knew she would do something to get back at me. I tossed from one side to the other, imagining the worst. In the twilight between wake and sleep, a thought hit me: maybe Annie had described her revenge in her diary! I could have a quick read to find out what she had in store for me!

The next thing I knew I was sneaking into Annie’s room. I heard her in the den watching TV with the rest of the family. I wondering whether she had put the diary back under her mattress. Cynthia sat stiffly on Annie’s pillow. I slid my arm under the mattress, careful to keep my face away from Cynthia who was suddenly way too close to me. But the diary wasn’t there. And I couldn’t pull my arm out from under the mattress! I was stuck! It had me!

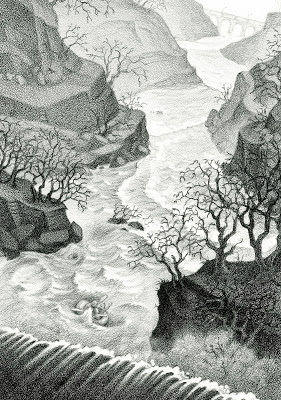

And to my horror, Cynthia was growing larger and larger. Her unusually huge wooden foot flopped off the bed while her wiry hair scratched the ceiling. Her lacy wedding dress brushed my face making me pull away in revulsion. She lumbered up off of the bed, her long arms swinging apelike from her marionette body. Cynthia opened her mouth and her sharp, pearly teeth flashed. A voice hissed loudly from Cynthia’s mouth:

Fiddle-faddle-flit-and-flutter, I smell the lie of her little brother, If I catch him near her bed I’ll pluck his eyes and stomp his head!It took every ounce of strength I had to pull my arm free from the mattresses. I ran from the room, my heart drumming in my chest.

The house shook as Cynthia’s couch-sized feet thundered after me. I was too afraid to look back, but I could hear her skirts brushing along the walls, growing ever closer. I knew she was gaining on me.

“Fee-fi-fo-fum,” she bellowed. “FEE-FI-FO-FUM!”

Her immense hand closed tightly around my body and hoisted me into the air. She held me so fast that I was helpless. I was entirely immobile in the marionette’s death grip. All I could do was close my eyes. I felt her cold, dry fingernail stroking my forehead, inscribing it with her signature of doom.

Her hot breath crawled into my ear and down my neck as she whispered:

Feeble-fible-fabble-fubble I smell one’s been making trouble, Naughty boys I like the most, Nicely broiled AND SERVED ON TOAST!I opened my eyes just in time to see her unlatch the door of her blazing oven, ready to shove me in.

My screams woke me up. Moonlight streamed through my window. The TV blared in the den. Strangely, I still couldn’t move. To my confusion, I found myself rigidly wrapped in my bed sheet, and tied ‘round and ‘round with Annie’s old jump rope.

Annie!

I scooted to the edge of the bed, jumped out, and wiggled and wriggled my way out of the cocoon Annie had fashioned for me. I flipped on the light and squinted back its sudden brightness.

When I looked in the mirror, there was heavy black writing on my forehead, scrawled in the garbled language of giants. It read:

!FFO SDNAH