“My name is Mrs. Artemisia Blount Walton and I’m visiting from Sheperd, Michigan, where I lived for 73 years,” she said. “I am 97 years old and am the oldest pioneer in the county. Sheperd lies in Isabella County, smack dab in the middle of the Michigan mitten.”

She raised her left hand, palm facing away from the students, and with her right, pointed to the spot just above her left hand’s middle knuckle, the place where Shepherd would be.

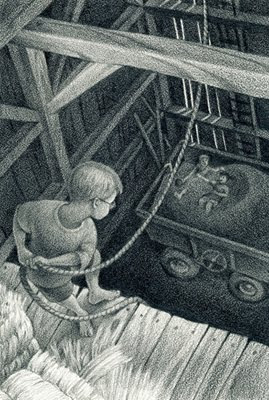

“When I was twenty-four years old I married John Billings Walton. He was a strapping young man with a furious head of auburn hair and a woolly beard to match. He had recently acquired 160 acres of land for $80.00 in the wilderness of Isabella County. So, as a young bride, Billings moved me from my parents’ home in Troy into the wildernss. We set out in a wagon pulled by oxen, over tortuous trails, and arrived nearly two weeks later at the log cabin he had built for me.”

“Maybe she’s related to Abraham Lincoln,” heckled a boy in the back.

But she continued, oblivious of the comment.

“The cabin was in the middle of a great forest; it had one room, a large stone fireplace, and a simple dirt floor. Our nearest neighbors were miles away and hard to reach. The closest post office was in St. Johns, a day’s journey to the south. There were many bears, wolves and Indians in the woods. We hauled our water from the nearby Salt River.”

Mrs. Walton stepped from a bright ray, disappearing momentarily into the classroom’s dark shadows.

“With our oxen, we began clearing land,” she continued. “Little by little, the level patch surrounding our cabin grew larger and larger. Within three years we had cleared enough land to build a one-room schoolhouse. Pupils came from far and wide, walking miles on Indian trails to attend. I earned $1.50 a week for teaching back then.

“In 1863 Billings entered the service during the Rebellion. I had two little children at that time, but managed to maintain the farmstead as well as teach while Billings was off fighting. In June the following year, Billings survived the Battle of the Wilderness only to be shot in his left hand at the battle of Petersburg. He was taken to Harwood Hospital in our nation’s capitol, but was transferred to Haddington in Philadelphia where his little finger was amputated. Billings was luckier than most other soldiers — he returned home after the war with only a finger missing.

“We had four more children after that. Our youngest son, Willard, was the great-granddad of your own classmate, Danny Powers.”

Everyone’s heads turned to look at me in disbelief as she continued.

“Billings died in 1879 and is buried in Salt River Cemetery,” she said wistfully. “I’m buried right next to him.”

Heads shot back around to the front of the class just in time to see Mrs. Walton fade from sight as she stepped out of the bright morning sunshine.